Articles, Mucus-free Lifestyle, Mucusless Diet, Writings about Arnold Ehret

Mucus-free, The ORIGINAL Vegan Diet!

Prof. Arnold Ehret is the true originator of the first widely publicized and successful “vegan diet,” yet he has been largely written out of the history of veganism. Veganism may be defined as the practice of abstaining from the use of animal products, particularly in diet, and is often coupled with a philosophy that rejects the commodity status of animals. In general, followers of plant-based lifestyles have come to be known as vegans. Although the term vegan was not coined until 1944 by Donald Watson, English animal rights advocate and founder of the Vegan Society, historians of veganism often consider lifestyles that fit modern definitions of the concept to be early representations of the vegan diet.

Standard historical narratives acknowledge that famous figures and cultures from the past may have fit the definition of “vegan,” including Pythagorous and other members of ancient Greek and Roman societies. More advanced narratives may also point out the high probability of the existence of plant-based communities from non-Western cultures that predate the Greeks. Yet, irrefutable evidence of the extent to which certain peoples were “vegan” is hard to obtain.

In 1806 Dr. William Lambe, who is sometimes credited as the father of veganism, changed his diet to a plant-based diet. In 1811 John Frank Newton, a patient of Lambe, published Return to Nature, which expanded on Lambe’s ideas and included ethical values towards all animals. In 1838 James Pierrepont Greaves opened Alcott House Academy, a school in London run entirely by principles proposed by Lambe and Newton. In 1842 the first confirmed use of the word ‘vegetarian’ occurred in the Alcott House journal. Yet, it is argued that the earliest to identify with the term “vegetarian” were practicing “vegan” lifestyles (See John Davis, “World Veganism: Past, Present, and Future“). Soon, attempted vegetarian communes, such as “Fruitlands” started to emerge. In 1874, Dr. Russell Trall published The Hygeian Home Cookbook, which is often considered to be the first vegan cookbook.

In “No Animal Food: The Road to Veganism in Britain, 1909-1944,” historian Leah Leneman (1999) explained that a faction of the vegetarian movement in Britain believed that refraining from “eating flesh, fowl, and fish while continuing to partake of dairy products and eggs was not going far enough (Leneman, 219).” The Vegetarian Society in Britain was formed in 1847 to promote the ideology of non-meat eating, although dairy products and eggs were viewed as permissible to eat since it was not necessary to kill the animals (Leneman, 219).

He pointed out that by 1909, vigorous debate occurred within the Vegetarian Society’s journal, The Vegetarian Messenger and Health Review (TVMHR) regarding the extent to which dairy and eggs should be considered part of a vegetarian lifestyle. Leneman asserted that C.W. Daniel published the first vegan cookery book, Rupert H. Wheldon’s No Animal Food: Two Essays and 100 Recipes, in 1910 (Leneman, 220).” Leneman points out that the book was largely forgotten, and that Fay K. Henderson’s Vegan Recipes (1946) was believed to be the first book to promulgate animal-free cooking (220-21).

Following years of contentious debates among members of the Vegetarian Societies about the elimination of dairy and eggs from the list of acceptable vegetarian foods, in August 1944 several Vegetarian Society members, including Donald Watson, asked that a section of its magazine be devoted to non-dairy vegetarianism. When the request was rejected, Watson suggested setting up his own quarterly newsletter. Watson issued the first newsletter named “Vegan News” in November 1944, where he combined the first three letters of ‘vegetarian’ with the last two. Watson said later that the word vegan represented the “the beginning and end of vegetarian.” (Interview with Donald Watson)

The Lacuna (Missing Information)

Related historical narratives of the origin of veganism often focus primarily on vegetarian societies and communities of Britain and the United States. However, this approach is incredibly limiting, and fails to acknowledge the important roles of the German Back-to-Nature movement, naturopathy, and the natural hygienic movement.

The Back-to-Nature Renaissance was a social, counter-cultural movement that began in the late 1800s, originally led by German youth. In the wake of the European industrial revolution, young activists rejected urbanization and middle-class social norms. Inspired by works of Nietzsche, Goethe, Hesse, and pagan “nature” religions, thousands of German youth endeavored to return to a more natural way of life in tune with natural laws. This caused great advancements in the area of natural healing, as many began to research and experiment with fasting cures and plant-based fruit and vegetable diets (vegan diets) as a sustainable way to live. (See Gordon Kennedy’s Hippie Roots and Children of the Sun, 1998)

Mucusless Diet : Early Plant-based Vegan Diet

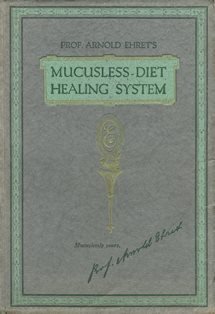

Natural healers and back-to-nature advocates such as Arnold Ehret had a profound influence on American youth, and spurred on the countercultural revolution in the United States and Europe, as well as the cultivation of naturopathy, the natural-hygienic movement, and the 1960s hippie culture. Following his vigorous experimentation with, and analysis of, the vegetarian and other natural healing diets of his day, Ehret coined the term Mucusless Diet to describe his plant-based, mucus-free diet of healing. Ehret proclaimed that meat, dairy products, and grains were mucus-forming because they decomposed into slimy waste, whereas mucus-free fruits and vegetables did not. His Mucusless Diet Healing System was the first successful approach of its kind to systematically combine a transition diet of non-mucus-forming plant-based foods with fasting to engender healing and higher levels of vitality. And by Ehret’s definition, mucus-free foods are plant-based. The scope of Ehret’s healing system was comprehensive and included what may be viewed as vegetarian, vegan, and fruitarian levels of eating for the purpose of permanently transitioning to a mucus-free, vegan diet. In other words, certain mucus-forming foods, particularly vegan ones such as grains, were suggested to be used during the “transition diet,” which can last indefinitely. Ehret asserted that the body “does not assimilate a single atom of any food substance that is not derived from the vegetable or fruit kingdom (Arnold Ehret, Annotated Mucusless Diet Healing System).”

My thesis of Mucus-free being the “ORIGINAL Vegan diet” is twofold. First, it rests on the assertion that Ehret’s works provided the first comprehensive plant-based system and ‘diet’ that could be replicated by large groups of people. Although there were people identifying as vegetarian that may have been eating what would be described as vegan, as well as a couple plant-based cookbooks published, there was no systematic or universally proscribed plant-based ‘diet’ that I could find. Second, mucus-free is now, and has always been, plant-based (vegan). Even before Ehret coined the term mucusless (mucus-free), anyone eating a plant-based diet that also excluded mucus-forming items was eating mucus-free and vegan.

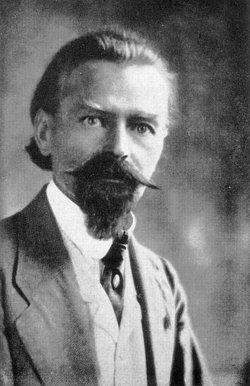

Arnold Ehret, Originator of the First Vegan Diet

Arnold Ehret was born July 25, 1866, near Freiburg, in Baden, Germany. At the age of 31, he was diagnosed with a terminal case of Bright’s disease (inflammation of the kidneys) by 24 of Europe’s most respected doctors. He then explored natural healing and visited sanitariums to learn holistic methods and philosophies. In a desperate attempt to quench his misery, Ehret decided to stop eating. To his amazement, he did not die but gained strength and vitality.

In 1899, he traveled to Berlin to study vegetarianism, and where he visited 20 vegetarian restaurants, and the Lebensreform co-operative at ‘Eden’, a vegetarian fruit colony in Oranienburg. He took courses on physiology and chemistry at a university of medicine and explored natural healing. This was followed by a trip to Algiers in northern Africa where he experimented with fasting and fruit dieting. Due to his new lifestyle, Ehret completely cured himself of all of his diseases and began using his methods to help others. His discovery caused him to posit that pus- and mucus-forming foods are the fundamental cause for all human illness, and that fasting (simply eating less) and a plant-based mucus-free diet is Nature’s primary method of cleansing the body of the effects of unnatural eating.

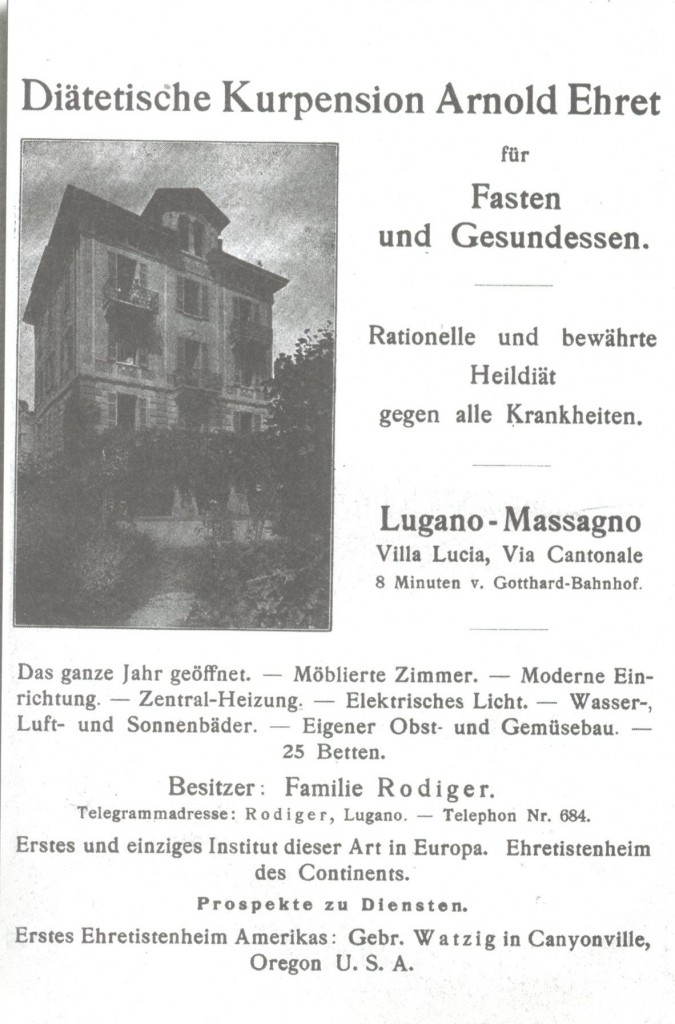

In the early 1900s, Ehret settled in a community of vegetarians, hygienists, naturists, and collaborated with Henri Oedenkoven who owned a sanitarium at Monte Verita. Ehret soon opened his own sanitarium in Ascona, Switzerland and another ‘fruit and fasting sanitarium’ in nearby Lugano (Massagno) where he treated thousands of patients considered incurable by conventional medical practitioners. Ehret soon became one of the most in-demand health lecturers, journalists, and educators in Europe, and his work helped save the lives of thousands of people. His controversial work forced natural health enthusisits into two camps: Ehretists and Non-Ehretists (See Kennedy, “Still Ehret”).

Although Ehret may have some articles on diet and healing that predate 1910, along with testimonials of his methods that date as early as a March 27, 1907 edition of Belgium newspaper (See The Cause and Cure of Human Illness By Arnold Ehret, translated by Ludwig Fischer, 2001) his famed Kranke Menschen (literally “Sick Human-beings”) was first published in 1910. On June 27, 1914, just before World War I, Ehret left from Bremen for the United States to see the Panama Exposition and sample the fruits of the continent. He found his way to California, which was of special interest to him. This was because the region was undergoing a horticultural renaissance due to botanists like Luther Burbank, who later paid tribute to Ehret. When the war prevented Ehret from returning to Germany, he settled in Mount Washington (Los Angeles), where he prepared his manuscripts and diplomas in his cultivated eating gardens. He and other “Back to Naturists” began to influence local populations of young people to investigate plant-based, vegan living.

Ad for one of Arnold Ehret’s Plant-based Sanitariums

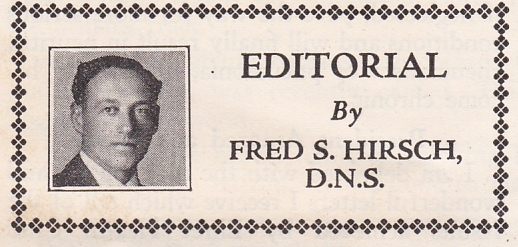

Fred Hirsch and Highland Springs Resort

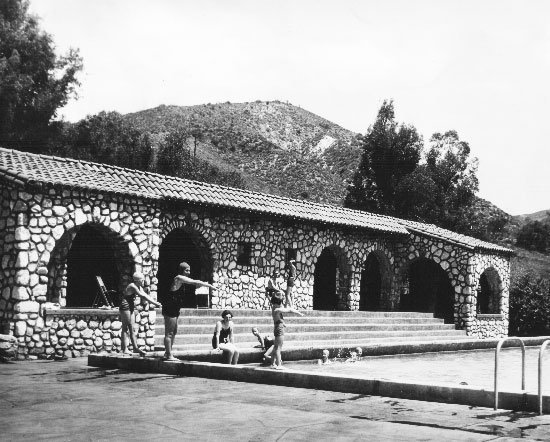

Fred Hirsch attended one of Ehret’s lectures in 1915 with the help of his brother. He was diagnosed with necrosis of the achilles, caused by a serious bone infection affecting both heels (Gordon, Still Ehret). Following a fasting session overseen by Ehret, Hirsch was heeled and threw away his crutches (Gordon, Still Ehret). Hirsch, who knew some German, then became the publisher and promoter of Ehret’s work for the next 60 years. In 1927, Fred, and his brother William Hirsch, bought property in Southern California and developed a vegetarian/vegan health resort called Highland Springs Resort. The restaurant on the resort was plant-based, and Hirsch grew much of the produce served there on the property. He also grew his own grapes and operated a small vineyard. “The resort became known as ‘The Last Resort'” as many sick people who were not able to get well with traditional methods, were able to get healthy through Hirsh’s health practices while staying at the resort (See History of Highland Springs Resort).” The resort was prominent with famous guests regularly attending, such as Dr. Albert Einstein, who was known to be close friends with the Hirsch family, as well as stars Bob Hope, Elizabeth Taylor, Ernest Hemingway and Roy Rogers (Highland Springs History, see also “Genius idea: Spend time at Highland Springs Resort”).

Conclusion

While the lifestyle known today as veganism was being debated among members of the British and American Vegetarian societies, students and authors influenced by Ehret’s work were already living plant-based, cruelty-free lifestyles. The Mucusless Diet Healing System was already touching the lives of thousands of people. Why are Ehret and other early proponents of plant-based living prior to 1943 often not recognized by historians of veganism? It appears that efforts have been made to systematically write Ehret’s fundamental contributions to diet, natural healing, and culture out of many historical threads. Detailed explanations and explorations of this question are beyond the scope of this article. Historically, professional and academic societies have sought to control historical narratives to further their own interests and position themselves as central figures. Despite the related plant-based vegan activities of members of the back-to-nature movement, natural hygienic associations, vegetarian/vegan societies, plant-based Rastafari movement (originating c. 1930), biblically based diet communities, etc., comprehensive analysis is often lacking and certain factions privilege narratives that include certain details and exclude others. Societal factions of economic class, race, gender, and industry, along with the cliquish culture of professional/academic societies, have all contributed to limited historical narratives of the origins of plant-based lifestyles, i.e. veganism.

Above, I’ve shown how limiting the general histories of plant-based living are, and have reexamined the history to situate Arnold Ehret’s contributions within the history. Long before Donald Watson coined the term “vegan” and while British Vegetarian Society members were arguing about the usefulness of dairy and eggs, Ehret’s plant-based methods and lifestyle was healing thousands of people, and influencing some of the most influential minds of the 20th century.

Resources

Davis, John. 2010-12. World Veganism – Past, Present, and Future: A Collection of Blogs. John Davis, (retrieved 12/2/14 from http://www.ivu.org/history/Vegan_History.pdf).

Ehret, Arnold. 2001. The Cause and Cure of Human Illness. Translated by Dr. Ludwig Max Fischer. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Ehret Literature Pub.

Ehret, Arnold. 2013. Prof. Arnold Ehret’s Mucusless Diet Healing System: Annotated, Revised, and Edited by Prof. Spira. Prof. Spira, ed. Columbus, OH: Breathair Publishing.

Kennedy, Gordon. 1998. “Arnold Ehret.” In Children of the Sun: A Pictorial Anthology, from Germany to California; 1883-1949, 144-153. Ojai, CA: Nivaria Press. (Also see Kennedy’s article, “Hippie Roots & The Perennial Subculture.”)

Kennedy, Gordon. 1999. “Still Ehret After all these Years.” In Just Eat an Apple, Issue 8. See “Still Ehret“.

Kennedy, Gordon, and Kody Ryan. May 13, 2003. “Hippie Roots & the Perennial Subculture.” Hippy.com, May 13. View it at “Hippie Roots.”

Leneman, Leah. 1999. “No Animal Food: The Road to Veganism in Britain, 1909-1944.” Society & Animals 7, no. 3: 219. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed December 3, 2014).

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. 2012. The Oxford Handbook of Food History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Check out the New Annotated, Revised, and Edited Edition of the Mucusless Diet Healing System from Amazon.

Pingback: Questions about the Annotated Mucusless Diet's Vegetarian Recipes Lesson - Mucus-free Life LLC